Coordination difficulties

Developmental co-ordination disorder (DCD), also known as dyspraxia, is a condition affecting physical co-ordination.

It causes a child to perform less well than expected in daily activities for their age, and appear to move clumsily. DCD is thought to be around 3 or 4 times more common in boys than girls, and the condition sometimes runs in families.

Dyspraxia or Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD)?

While many people in the UK use the term dyspraxia to refer to the difficulties with movement and coordination that first develop in young children, this term is used less often by healthcare professionals.

Instead, most healthcare professionals use the term developmental coordination disorder (DCD) to describe the condition.

This term is generally preferred by healthcare professionals because dyspraxia can have several meanings.

For example, dyspraxia can be used to describe movement difficulties that happen later in life because of damage to the brain, such as from a stroke or head injury.

Some healthcare professionals may also use the term specific developmental disorder of motor function (SDDMF) to refer to DCD.

Symptoms of DCD

Early developmental milestones of crawling, walking, self-feeding and dressing may be delayed in young children with DCD.

Drawing, writing and performance in sports are also usually behind what is expected for their age.

Although signs of the condition are present from an early age, children vary widely in their rate of development. This means a definite diagnosis of DCD does not usually happen until a child with the condition is 5 years old or more.

Problems in infants

Delays in reaching normal developmental milestones can be an early sign of DCD in young children. For example, your child may take slightly longer than expected to roll over, sit, crawl or walk.

You may also notice that your child:

- shows unusual body positions (postures) during their 1st year

- has difficulty playing with toys that involve good co-ordination, such as stacking bricks

- has some difficulty learning to eat with cutlery

These signs might come and go.

Problems in older children

As your child gets older, they may develop more noticeable physical difficulties, plus problems in other areas.

Movement and co-ordination problems

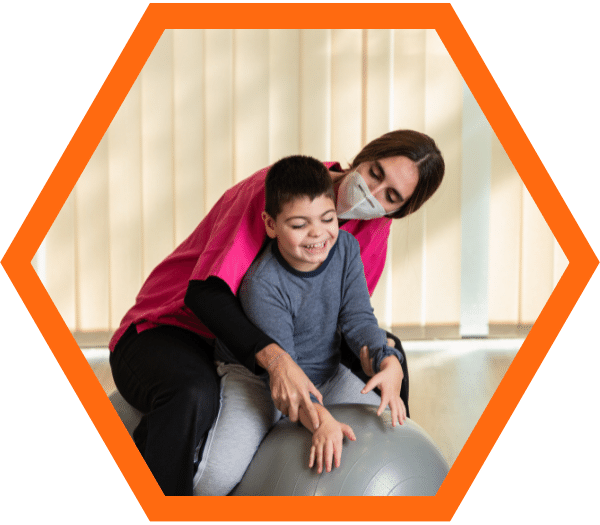

Problems with movement and co-ordination are the main symptoms of DCD.

Children may have difficulty with:

- playground activities such as hopping, jumping, running, and catching or kicking a ball. They often avoid joining in because of their lack of co-ordination and may find physical education difficult

- walking up and down stairs

- writing, drawing and using scissors – their handwriting and drawings may appear scribbled and less developed compared to other children their age

- getting dressed, doing up buttons and tying shoelaces

- keeping still – they may swing or move their arms and legs a lot

A child with DCD may appear awkward and clumsy as they may bump into objects, drop things and fall over a lot.

But this in itself isn’t necessarily a sign of DCD, as many children who appear clumsy actually have all the normal movement (motor) skills for their age.

Some children with DCD may also become less fit than other children as their poor performance in sport may result in them being reluctant to exercise.

Additional problems

As well as difficulties related to movement and co-ordination, children with DCD can also have other problems such as:

- difficulty concentrating – they may have a poor attention span and find it difficult to focus on 1 thing for more than a few minutes

- difficulty following instructions and copying information – they may do better at school in a 1-to-1 situation than in a group, so they can be guided through work

- being poor at organising themselves and getting things done

- being slow to pick up new skills – they need encouragement and repetition to help them learn

- difficulty making friends – they may avoid taking part in team games and may be bullied for being “different” or clumsy

- behaviour problems – often stemming from a child’s frustration with their symptoms

- low self-esteem

Although children with DCD may have poor co-ordination and some additional problems, other aspects of development – for example, thinking and talking – are usually unaffected.

Causes of DCD

Any problem in this process could potentially lead to difficulties with movement and coordination. It’s not usually clear why coordination doesn’t develop as well as other abilities in children with DCD.

However, a number of risk factors that can increase a child’s likelihood of developing DCD have been identified. These include:

being born prematurely, before the 37th week of pregnancy

being born with a low birth weight

having a family history of DCD, although it is not clear exactly which genes may be involved in the condition

the mother drinking alcohol or taking illegal drugs while pregnant

Support for educational settings

A range of support for educational settings can be found on the Bromley Education Matters website, including checklists, guides and posters.

Who to talk to if you have concerns

If necessary, they can refer your child to a community paediatrician, who will assess them and try to identify any developmental problems.